The United States Map Ok Google Tell Me if the Twin Towers or Build Again From the 911

After voting in the New York City primary election on the morning of September eleven, 2001, Alan Leidner, then the director of Citywide Geographic Data Systems (GIS) at the New York City Department of It & Telecommunication (DoITT), entered the subway virtually his polling place. He exited into a dissimilar world.

The train stopped just brusk of the Chambers Street-World Merchandise Center station, near Leidner's function, and began to inexplicably move in reverse, finally discharging passengers at 14thursday Street, a few miles uptown.

"I walked out and saw the billowing smoke from the site, and realized I couldn't come across the towers," he recalled. "Somebody said they'd come down, and I idea 'Nah, that can't be.' But when I looked closer, information technology was clear they were no longer at that place."

He began the long walk home to the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Soon after he reached his flat, he took an incoming call on his jail cell telephone. Information technology was Larry Knafo, director of the New York City Part of Emergency Management (OEM).

At the moment of the metropolis'due south about dire emergency, OEM was an agency without an office. The 7 World Merchandise Center building it had occupied stood in the shadow of the Twin Towers. OEM staff had made it out a few hours earlier their edifice collapsed, just they had to leave data and computers backside.

While Knafo struggled to reconstitute OEM at an alternate location, he had a request for Leidner.

"We demand maps," he said. "Can yous brand some?"

Building the Basemap

Leidner was non himself a mapmaker. An urban planner by training, he oversaw the city's advanced GIS. Throughout the 1990s, he led a defended interagency team that created a singular map of America's largest metropolis.

One way to conceive of a city is every bit a series of informational layers, each represented by unique sets of locations on a mutual canvass. Some layers correspond tangible data such as addresses, sidewalks, and power lines. Others provide data that is less immediately credible, like air quality, demographics, and crime statistics. What all the layers share is a location component.

Leidner and a small team of GIS acolytes—including Wendy Dorf, a manager at the city's Department of Ecology Protection who supervised the cosmos of an extensive GIS map of the city's water supply organisation—understood that no typical map could represent all the city's data layers. A digital map built with GIS, yet, could include all layers in a way that counterbalanced complication with the clarity of visualization.

-

Handheld mapping apps were used collect data almost debris and homo remains found on the Ground Zero site. (Image courtesy of Sean C. Ahearn, CARSI)

Influenced by similar projects in San Diego and Seattle, Leidner's group consisting of consultant Jim Hall and local City GIS experts including Dan McHugh (Metro Transit Authority), David Litvin (DoITT), and Paul Katzer (Parks), began to build NYCMAP, a basemap of New York City. The map incorporated more than vii,500 aerial photographs and vector layers derived from the imagery that included city streets, properties, building footprints, transportation networks, rivers, and other waterways. It would ever exist a work in progress—with new data sets added equally they became available—only by 1999, NYCMAP had reached a phase of tentative completion. With 50 available layers, it was one of the more advanced city maps in the world.

Midnight Mapping on Twenty-four hours 1

Two years before the assail, every urban center agency had received access to NYCMAP, including the Phoenix Unit, the Burn Department of the City of New York'due south (FDNY) GIS division. Inside an hr of the towers' collapse on September 11, 2001, the FDNY used it to create a grid of the disaster site, to help orient first responders.

OEM leadership now needed Leidner and his team to rapidly produce more detailed maps of the World Trade Eye complex, generated from the basemap. Leidner connected with Sean Ahearn, a geography professor and GIS practiced at the Metropolis University of New York'due south Hunter College who was the steward of the basemap, having designed it alongside experts at PlanGraphics and managed the aeriform imagery and photogrammetric work of Sanborn. Ahearn had done much of the technical piece of work on the basemap at his lab, the Center for Advanced Research of Spatial Information (CARSI), and had the definitive and just attainable copy on figurer disks in his part.

Leidner, Ahearn, and a few others worked until midnight that aforementioned 24-hour interval generating maps of the area presently to exist known throughout the world as Ground Zippo. At 6:xxx the adjacent forenoon, with the smoke however rise from the rubble, they loaded three big computers into two police cruisers, which ferried them to OEM'southward temporary home at the New York City Police force University. Wendy Dorf and Jack Eichenbaum, another local GIS expert, began calling and emailing anyone they could retrieve of in the local GIS community to lend their expertise and mapping skills.

"We brought in a lot of volunteers," said James McConnell, OEM'southward GIS director. "We'd requite them assignments, similar adding new field data to maps and customizing data layers to fulfill specific mapping requests that supported field operations."

By the end of the week, the group had coalesced into the Emergency Mapping and Data Middle (EMDC), role of an emergency response center occupying Pier 92 on the Hudson River, 5 miles upward the West Side Highway from Footing Zero. Every 24-hour interval, at all hours, as many as 100 GIS professionals and volunteers passed through EMDC, liaising with metropolis, state, and federal response personnel who needed maps and information for everything from logistics to debris removal.

-

Within the first month following 9/eleven, there were 50 standard production maps that were each modified at least every other solar day. Hundreds of copies of these maps were distributed and more than than 50 percentage of the maps were customized to the unique involvement of the requestor. (Image courtesy of Sean C. Ahearn, CARSI)

It was a profoundly unsettling time, with rumors spreading of farther terrorist attacks. Because the center was considered a prime target, soldiers with automatic weapons guarded the doors while armed patrol boats stood fix on the river.

In the early days of the recovery attempt, Leidner and his squad expended considerable effort spreading the word, demonstrating the value of maps with city agencies. As more information was gathered, the maps grew in complexity, with layers from city agencies added to the existing basemap.

"Pretty soon, we were churning out hundreds of maps a day plus analyses, all dependent on being able to register data to the basemap and integrate it with other layers," Leidner said.

Wendy Dorf'southward team focused on hush-hush infrastructure, a difficult suggestion that involved importing utility company blueprints and detailed building plans, synchronizing conflicting data formats, and filling in gaps caused by missing or incomplete data. Making sense of hugger-mugger connections became crucial to public safety and to those repairing the damage.

"Thank goodness that basemap was created in the '90s," Ahearn said. "Otherwise, we would've been severely hampered."

Extending Mapping's Possibilities

The circumstances of 9/eleven forced the GIS teams to exam applied science'southward limits. Everyone understood the importance of apace capturing data and providing updates to responders and the thousands of families who had lost loved ones. GIS tools were used to collect near existent-time updates, logging locations of debris and human remains.

In prior years, the California Governor's Part of Emergency Services (Cal OES) had emerged as a national leader in treatment disasters. The agency had gained special notice for its groundbreaking work in 3D modeling in the days following the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma Metropolis.

On the 24-hour interval after the nine/xi attacks, Dave Kehrlein, Cal OES'south GIS manager, flew from Sacramento to Washington, DC, to assist federal investigators apply similar methods to the Pentagon crash site. He and so traveled to New York to aid the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) with the growing GIS effort at Footing Zip.

Within days of the formation of the Pier 92 center, FEMA'due south urban search-and-rescue team had established a staging expanse at the nearby Jacob K. Javits Convention Center.

In the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, FEMA'south urban search and rescue team had mapped the immediate boom site, while city officials handled the area beyond the perimeter. Under the guidance of Kehrlein and Ron Langhelm, FEMA's GIS coordinator, a similar division of labor developed in New York Metropolis after 9/11.

"We mapped Ground Zero, including all the operations and logistics," Kehrlein explained. "Leidner's team mapped everything outside the area, helping to get those buildings inhabitable and open for business concern, because a lot of them were damaged by things like window blowouts and flying debris."

-

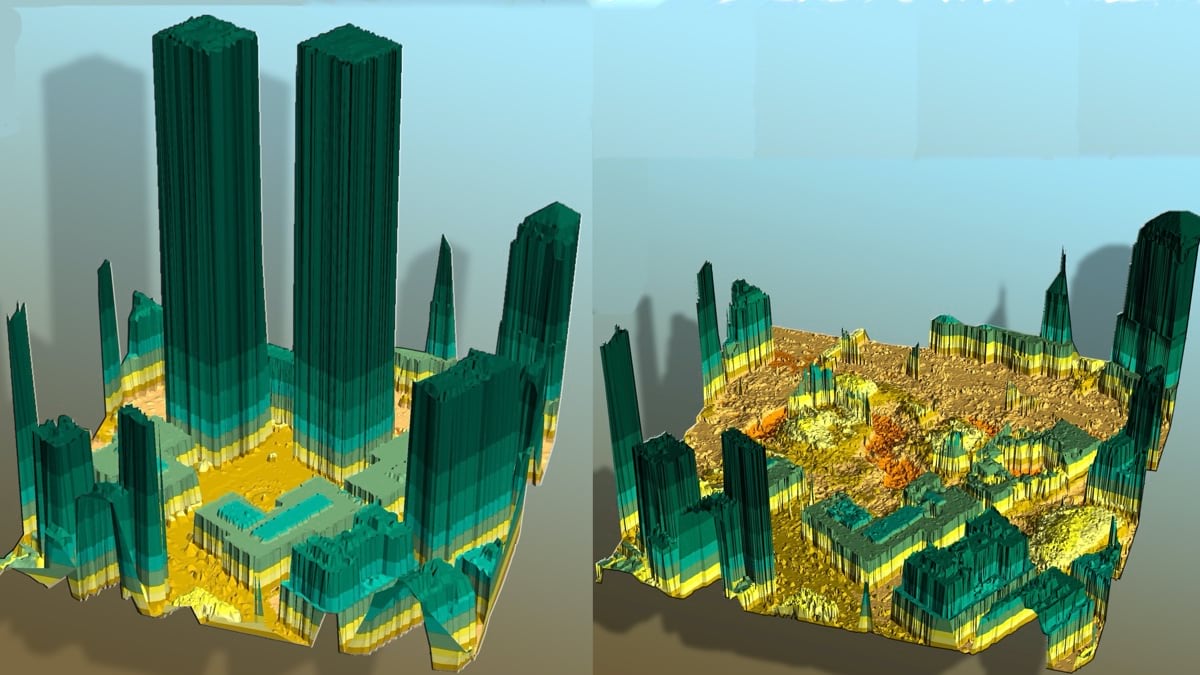

Lidar had a coming-of-age moment during 9/11 considering the remote sensing tool provided precise measurements and the first clear moving-picture show of the damage equally this laser-based sensor could cut through the heavy smoke rising from the site. Lidar was also flown shortly before the disaster, so a comparison map was fabricated to clearly show the scale and telescopic of the impairment. (This map was created by Sean C. Ahearn and Jeffrey Bliss at the Eye for Advanced Inquiry of Spatial Information, Hunter College)

The Earth Trade Center was a symbolic target for a terrorist assail, but equally the anchor of one of the world'due south major fiscal districts, it was also a strategic i. Each day that was unsafe for people to move through the financial district represented a damaging bear on to the metropolis, nation, and globe economies.

Using GIS tools, the team helped speed a building inspection process that would otherwise have proceeded slowly—investigators filling out and filing paper forms every bit they moved from edifice to edifice, examining the amercement. Instead, Ahearn collaborated with the geospatial company LinksPoint to develop 1 of the earliest mobile GIS apps, accessed via PDAs (the precursor to today's smartphones). "It went from a 2-twenty-four hours lag to our beingness able to do an assessment of all the buildings in an expanse and sending that map to the mayor by noon," he said.

In addition to their work making maps for start responders, the GIS experts at Pier 92 provided a portfolio of maps for media outlets and public distribution. Many of the map outputs were first-of-their-kind products—including constantly updated digital maps—that helped illustrate the aftermath of the attacks. New York Metropolis mayor Rudy Giuliani also used maps to communicate the changing conditions at Ground Zero to the public.

Subterranean Dangers

Equally the days passed, GIS experts kept finding new uses for the applied science to support critical inquiries. A request came in to map all suitable buildings in the vicinity within 10,000 feet from Basis Naught that could be used as temporary morgues. Another response squad needed maps of the subway tunnels flooded past water main breaks, as structural engineers began to worry that Hudson River water could spread through the basements of destroyed buildings.

Perhaps the almost harrowing moments came when someone on Pier 92 mentioned at that place might be a tank under the site containing 100,000 gallons of Freon, the colorless and odorless gas used in the World Merchandise Heart'due south ac systems. Ongoing hole-and-corner fires, fed past oil and gas from the buildings' emergency power systems, threatened to reach the Freon tank.

Ahearn and others were able to map the fires' locations using thermal imagery from sensors aboard helicopters flown above the site. But they needed to locate the tank in relation to the fires. Freon, when exposed to heat, creates phosgene, a gas that was the fatal agent in most of the chemical weapons used in World War I. Give-and-take spread, and eventually GIS consultant George Davis located building plans that showed the location of the tank. Imported into GIS, that information immune firefighters to hose downward the area between the flames and the Freon, preventing further catastrophe.

Above footing, equally recovery efforts continued, GIS maps and aerial imagery guided daily work. Working with engineers and GIS specialists, Wendy Dorf assembled and collated hush-hush infrastructure location data that showed operators of cranes and other heavy machinery—and others working on the pile—where the earth may have become unstable due to nearby fires.

20 Years Afterward

New York Urban center's GIS teams provided crucial insights in response to the 9/eleven attacks, and their applications of the engineering science have grown more advanced since. At the World Merchandise Center site in 2001, teams assessing and recording response progress relied on fixed-fly airplanes with thermal imaging and other sensors to collect data daily under the supervision of New York Country GIS officials—which was processed in Albany (150 miles abroad). The disk drives were then driven back each morning time to the EMDC past land troopers. FDNY firefighters from the Phoenix Unit likewise shot digital photos while hanging from a helicopter's landing gear.

"Information technology was ane of those moments where the applied science went from being something used past a small-scale group of geospatial scientists to existence an integral function of how to manage a city—and, in this case, how to answer to an emergency," Ahearn said.

Today, disaster relief includes drones and cloud computing for image gathering and processing. High-speed networks forestall the cumbersome tapes and drives of the past. Many response teams are using drones to gather imagery in a way that's cheaper, safer, and more than flexible than helicopters. Drone images, also as lidar and other remotely sensed data, tin be swiftly and securely processed in the cloud and synced to a GIS map or application.

Looking back, McConnell recalls the emergency response to 9/11 and the work of many teams using GIS to bring fundamental information points together. "I think for many people, it was their offset existent exposure to GIS," he said. "Everybody was used to static maps. The fact that nosotros could have updated maps every day—focusing on exactly what people needed to focus on—was a new experience for a lot of responders and recovery people."

The Pier 92 group finally dispersed afterwards three months. "I can remember one of the terminal times I went to the site," Ahearn said. "I was standing with a firefighter on height of a building overlooking the World Trade Middle. We spotted a plane flying toward us, and nosotros held our breath."

Learn more about how GIS is used to safeguard public safe.

Source: https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/blog/how-maps-guided-9-11-response-and-recovery/

0 Response to "The United States Map Ok Google Tell Me if the Twin Towers or Build Again From the 911"

ارسال یک نظر